Awe in the new year (Rosh HaShanah Day 1, 5783/2022)

Let’s start by taking a vote on a very important issue. We are voting on the correct way to refer collectively to these days of Rosh HaShanah and Yom Kippur. Option #1 is to refer to them as the “High Holidays” - 2 words. Option #2 is to refer to them as the “High Holy Days” - 3 words. <VOTE>

There are various ways to address this question. You can do a Google search and you find that “High Holidays” - 2 words - has 1 million 600 thousand hits, whereas ‘High Holy Days’ - with 3 words - has a paltry 692,000 hits. So the people have spoken: “High Holidays” with two words is vastly more popular than “High Holy Days” with 3 words.

And yet -- “the people” are completely wrong. (In my humble but correct opinion.) High Holy Days is correct - and I will show you why.

The Hebrew words upon which this expression is based are Yamim Nora’im -- often translated as “Days of Awe,” because “nora’’ is a Hebrew word for “awe.” Yamim is “days.” If your preferred phase is “High Holidays,” then you are suggesting that these days are “holidays” that are especially important. But that’s not what the expression “Days of Awe” means at all. “Yamim Norai’m” means these are “days” of awe - or in other words, these are days of “high holiness.” Or in other words, these are highly-holy days - or High Holy Days.

I’m not proud of this, but whenever I see any writing of the synagogue that says ‘High Holidays,” I change them to “High Holy Days.” The result, of course, is that we’re inconsistent, and on our web site you can definitely find it spelled both ways. (But by the way: web sites are more likely to say “high holidays,” but prayerbooks and other books written by rabbis tend to say “high holy days.”

But why should this name matter? Because these days are not merely holidays. They are ‘yamim nora’im’ -- they are days of some kind of special emotion which we call “awe.” Rosh HaShanah and Yom Kippur have been called Yamim Nora’im, or Days of Awe, since the 15th century. A German scholar named the Maharil started to use this expression, though it is not found anywhere in the Torah in the Hebrew Bible or in the Talmud. But the expression caught on, and presumably it expresses something important about the qualities and character of this day.

Let’s investigate what this word “awe” means. It refers to an emotion -- not an emotion that is on the spectrum between happy and sad, but an emotion that is on the spectrum between lightweight and intense. (and of course it’s closer to ‘intense.’)

There are people who find “awe” to be an old-fashioned word describing an old-fashioned emotion, which people used to experience a long time ago before we better understood our world. But I don’t think there’s anything old-fashioned about “awe.” On the contrary - it may be easier for us to experience awe in our contemporary world than it was for our ancestors.

Actually, seeking out moments of awe -- and its related emotion of ‘wonder’ - are at the heart of what it means to be a religious person. A thinker especially associated with this idea is Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, who was the teacher of many of my teachers. He famously wrote that the central goal of all of a Jewish spiritual outlook on the world is promoting what he called “radical amazement,” a sense of wonder and awe at everything extraordinary about our world.

and he summed up the purpose of all religious ritual from his perspective: “All worship and ritual are essentially attempts to remove our callousness to the mystery of our own existence and pursuits.”

Awe is often associated with vastness in nature. When I think of the word “awe,” I am likely to think, for example, the immense waterfalls and great mountains and oceans I have been privileged to see, or even the stars when I have a chance to get a little further from the New York area and can actually see them. All these tend to be experiences of feeling tiny in the presence of something overwhelmingly vast and powerful.

Looking at stars is like a paradigm for this feeling. On the one hand, looking at stars is a glorious and relaxing quiet experience. And then on the other hand, once you think about it just a little bit, there’s almost no life experience that makes you feel smaller, even to the point of insignificance, than looking up at stars, each of which is roughly as large and ferociously powerful as our sun if not more so, or in other words, most of those beautiful and quiet stars are a million times larger than earth and are so hot that they would incinerate anything that got within about a million miles of them. And if the stars don’t seem that huge or that ferocious, it’s only because they are so incredibly absurdly far away from us - and by comparison all of life on earth is collectively a smear of chemicals on a tiny pebble hurtling through space.

Even thousands of years ago, our ancestors looked up at the stars and it made them feel small and insignificant. In Jewish tradition, this idea is expressed in Psalm 8 - כִּֽי־אֶרְאֶה שָׁמֶיךָ מַֽעֲשֵׂי אֶצְבְּעֹתֶיךָ When I look at your heavens, your handiwork, יָרֵחַ וְכוֹכָבִים אֲשֶׁר כּוֹנָֽנְתָּה: the moon and the stars which you have shaped - ה מָֽה־אֱנוֹשׁ כִּֽי־תִזְכְּרֶנּוּ וּבֶן־אָדָם כִּי תִפְקְדֶֽנּוּ: what are mortals, that you should be mindful of them, mere mortals, that you should take account of them?”

The author of that Psalm used to feel small when he looked at the night sky, and saw the moon and stars. But today we know that he was even smaller than he could have imagined. That’s one way we often describe the feeling of “awe” -- feeling in the presence of something so vast that it can hardly even be comprehended. This actually is our situation every day, though we often don’t think about it.

Some psychologists at the University of California at Berkeley have been especially interested in understanding awe -- including what makes people feel awe. These researchers have found that nature is one among many routes into experiencing awe. Awe can be inspired by learning about people of extraordinary talent or extraordinary goodness. It can be prompted by appreciation of art or music, and awe can be prompted by experiences in the context of a religious community - in part because it’s in religious communities that we’re likely to meet people who are inspiring in their goodness. And life cycle events often inspire awe (and are often celebrated in the context of religious communities). Giving birth or being present at a birth, or celebrating a birth, bar and bat mitzvahs and weddings and graduations all remind us that we, or people we love, are miraculously moving to a new life stage.

The team at Berkeley is also specially interested in what does the feeling of awe do to and for people? How do people act differently when they feel awe?. And they have devised a series of experiments to find out.

Here’s one example. It happens that near the Berkeley campus is a grove of the tallest eucalyptus trees in North America. And they would have the experiment subjects come to look at the eucalyptus trees - for a full 60 seconds - and then they would be asked some questions about their experience. And there was also a control group that was brought to the same spot but with their backs to the trees, and asked to look at a not very interesting university building for 60 seconds - and then they would be asked the same questions about their experience. But one of the experimenters, in the process of asking the questions, would -- “accidentally” but really on purpose -- stumble and drop a bunch of pens onto the ground. What was really being measured by this experiment was: who is more likely to help to pick up more pens: the person who has just been looking at some of the tallest trees in North America, or the person who has just been looking at a building? The answer, of course, is the person who has been looking at the trees is consistently likely to pick up more pens, even though they have no reason to believe that anyone is paying attention or that this act of kindness is in any way part of the experiment..

And the investigators consistently found, in this and similar experiments, that people who have had an experience of awe are less focused on themselves -- the experience of awe “leads people to cooperate, share resources, and sacrifice for others.” Psychologist Dacher Keltner of Berkeley writes: “Being in the presence of vast things calls forth a more modest, less narcissistic self, which enables greater kindness toward others.” Awe makes us more deeply connected to other people, less self-centered, and more likely to put others at the center.

This should not surprise us at all - in fact it’s exactly what the High Holy Day Mahzor tells us. In every Amidah in the Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur service, immediately after the Kedusha, we have a reference to awe; we read:

וּבְכֵן תֵּן פַּחְדְּךָ ה' א-לקנו עַל כָּל מַעֲשֶֽׂיךָ וְאֵימָתְךָ עַל כָּל מַה שֶּׁבָּרָֽאתָ

“Adonai our God, instill Your awe in all You have made and created,

וְיִירָאֽוּךָ כָּל הַמַּעֲשִׂים וְיִשְׁתַּחֲווּ לְפָנֶיךָ כָּל הַבְּרוּאִים.

so that all You have fashioned revere You,

and all You have created bow before You,

וְיֵעָשׂוּ כֻלָּם אֲגֻדָּה אֶחָת לַעֲשׂוֹת רְצוֹנְךָ בְּלֵבָב שָׁלֵם.

and all be bound together, carrying out Your will wholeheartedly.” (be-levav shalem -- that’s actually the line from the prayers that gives the Lev Shalem Mahzor its name.)

In other words, one of the effects of the entire world experiencing awe and reverence is that the entire world would be more likely to bond together, be less focused on themselves, more focused on the needs of others, more likely to make decisions that are the best for everyone, not just for ourselves. The psychological experiments and the Mahzor are in agreement.

If our world could use more concern for the needs of others, and more decision-making based on the needs of everyone, maybe our world could use more yir’ah - more awe. And the first step to having moments of yir’ah, of awe, even every day, is simply to open ourselves up to them -- which is one of the functions of berakhot, the blessings that punctuate a Jewish day, with a goal of reaching מאה ברכות בכל יום me’ah berakhot bekhol yom - one hundred blessings each day.

Research on awe suggests that we can have experiences of awe not only when we look at the natural world -which is always accessible to us - but we can also experience awe and reverence when we come into contact with extraordinary people, people who inspire us through their talents, their goodness and generosity.

So on these Days of Awe, I would like to tell you about 3 people, or categories of people, who inspire in me experiences of awe - of yir’ah. These people have each had a tremendous effect on our synagogue community. And I think that thinking about them will help us all to deepen our experience of yir’ah.

===============================

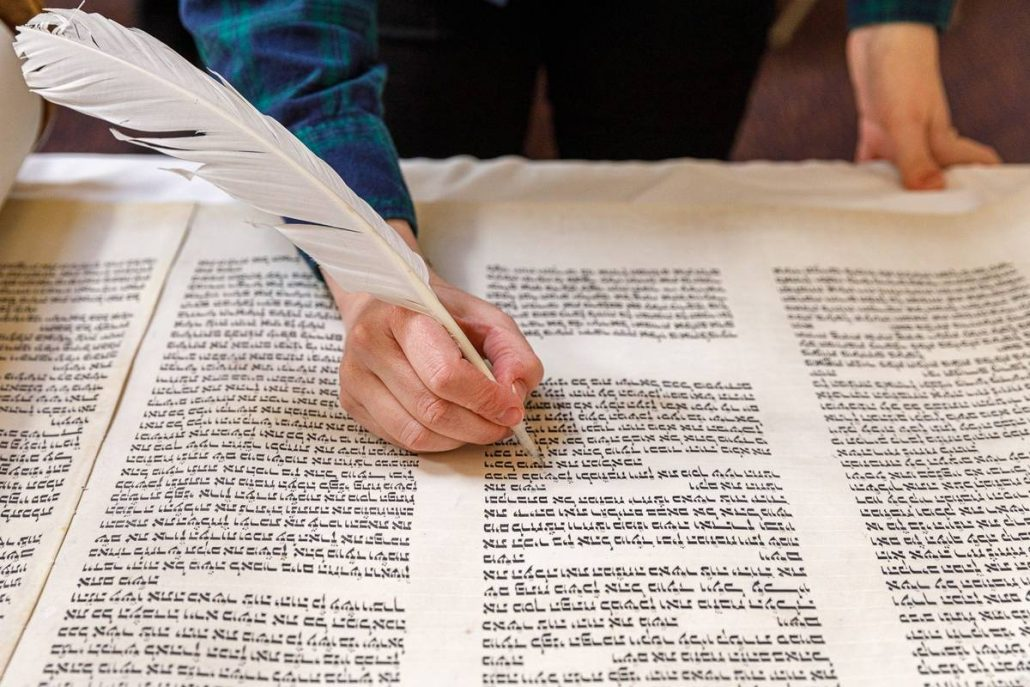

First, I am thinking of two people whose names I don’t know. One of them is definitely deceased, and the other is probably deceased. I am thinking of the Sofrim -- the Torah scribes -- who wrote the torah scrolls that we read from this morning -- one of which was probably written in Lithuania, 160 years ago, and one was probably written about 50-60 years ago, in the US or in Israel or possibly in Europe. Every letter in each of these scrolls was written on parchment by hand, with an ink and a quill pen that are identical to what was used to write torah scrolls thousands of years ago. The work that goes into writing a torah scroll has to be described as awe-inspiring. It could be assumed that most people who plan to write a Torah scroll have memorized most of the Torah -- and yet the scribe is not supposed to write any of it from memory, always reading every word from a printed text before writing it carefully, shaping each letter with exacting precision, for each of the hundreds of thousands of letters in the Torah. Torah scrolls are expensive, but when you remember that each scroll represents 8 to 12 months of full time work, plus materials that can be costly, you can see that no one is getting rich off of this work.

The scribe creates a remarkable hand-made, one of a kind, document in expert calligraphy. Reading from the torah reminds us that the torah is passed down from generation to generation, but also from individual to individual: from individual scribe, to individual reader, as we in our community - people of all ages - are reading words that an individual put down on parchment in such exquisite and precise fashion. Something else amazing is that Torah scribes never sign their work. That’s why we don’t know who wrote it. When I picture someone so devoted to the ideals of the Torah that they would spend that length of time immersed in the activity of writing so that words of Torah would be available to synagogues around the world - to be such a tangible link in the chain of Jewish tradition - and that they would do it anonymously - that’s something that fills me with reverence and even awe.

And the second person on my mind is here today - and that’s Susie Klein, who designs and creates our stained glass windows which are a remarkable part of this room and of our synagogue’s identity. We love taking visitors through to show them these unique windows, each one providing creative interpretations of the stories in the Hebrew Bible, while also being so innovative simply as examples of contemporary stained glass art, with their use of stones and shells.

It is a magical experience to see the process by which the designs and ideas form in Susie’s head, and gradually the sketch and design and the text are transformed into pieces of glass that are cut and shaped and assembled. Also remarkable is that Susie does this as a volunteer, leading a team of other volunteers who assist her in implementing her vision for these windows, creating not just something beautiful but creating numerous images in each window that make you think and make you appreciate the natural world. Like the scribes: Susie’s commitment to artistry, generosity of spirit, and religious dedication inspire reverence and even awe in me.

And the third person on my mind is someone who is not here today, but he has visited our community many times and spoken from this bimah several times to inspire us with his words. I am thinking of our friend Alain Mentha, a founder of the Welcome Home Jersey City organization that has transformed the lives of hundreds of families of refugees in the Jersey City area.

Alain’s father was from Switzerland, and during the Holocaust his family saved Jews fleeing from the Nazis, and that bit of family history gave Alain a life-long interest in helping refugees.

He and his family began volunteering with refugee resettlement immediately after the 2016 election, realizing that this was a program that the new administration would likely try to dismantle. With other friends and activists he created the organization Welcome Home Jersey City, for which he has served as the volunteer executive director for most of the past 6 years.

Picture yourself as a refugee (for Jews, this is not a stretch; most people of Jewish ancestry have at least some refugees in the family). You have been living under a government so repressive that you have fled the country, have been living in a refugee camp, and then applied for and received refugee status in the United States though you have never been there and you know no one there. You aren’t even sure who is going to pick you up at the airport, let alone where you’re going to stay immediately upon arrival, how you’re going to go shopping, open a bank account, register your kids in school, learn English, and find employment in your field. But if you’re assigned to arrive in Jersey City, New Jersey -- you’re soon paired up with volunteers who will help you do all these things, thanks to Welcome Home.

I get goosebumps when thinking about the hundreds of our neighbors in Jersey City -- from places like Eritrea, Iraq, Chad, and Syria, -- who have been so lovingly cared for by volunteers from Welcome Home at such a vulnerable time for them, in what is close to a dictionary definition of Chesed - lovingkindness expressed through tangible action.

So many people from our congregation invest countless hours in Welcome Home, including our members Bess Morrison and Fred Miller who chair the effort to help refugees to find employment, the members of our refugee support committee led by Hope Koturo, so many people who have volunteered at the Fun Club to help kids with homework and to help adults with English, including several bar and bat mitzvah students in the last several years who have done their Mitzvah projects in conjunction with Welcome Home and often reported that doing so has been among the very most impactful things they have done in their lives up to this point. (And it won’t surprise you that the caseload for Welcome Home has increased dramatically this year with the arrival of numerous Afghan refugee families. If you want to be part of the work of Welcome Home, fill out one or more of these volunteer forms.)

Our prayers right now are with Alain and his family as he faces a challenging health situation. I am in such awe at what he has achieved and at the enduring impact he has made in the lives of so many people in our community and our region.

A common denominator among all these people I have mentioned is that their achievements are magnified by the actions of others. The words written by the Torah scribe are only heard when our community’s torah readers read them. The actions of Susie with her stained glass, and with Alain with Welcome Home, are magnified by the many many partners who are inspired to work alongside them.

Early in the Torah, Jacob has a dream in which he comes to understand that earth and heaven are more closely connected than he had previously realized. And when he wakes up he says “God is in this place and I hadn’t realized.” He then says מה נורא המקום הזה - how awesome is this place.

He could have been talking about that spot - or the entire world. Or he could have been talking about THIS place - which is dedicated to helping people to find their sources of inspiration - and to become sources of inspiration and awe to others.

May your coming year of 5783 be filled with Yamim Nora’im - not just these High Holy Days, but many more days when you will find YOUR sources of awe and inspiration - in the natural world, in the expression of our values, and in encounters with people who can inspire you to be “highly holy.”

Shanah tovah!!

Comments

Post a Comment