"A blessing for the Czar?" -- in honor of July 4

My synagogue owns a set of huge mahzorim

– prayerbooks for Jewish holidays – that was printed in Lithuania in 1914.

I like to look at these books every

year as July 4 approaches. I carefully

turn their yellowed, crumbling pages until I get to the Prayer for the Government,

recited shortly after the reading of the Torah and Haftarah. And in this prayerbook, the prayer reads:

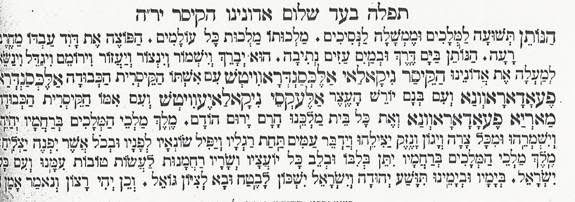

|

Mahzor Kol-Bo,

Vilna, 1914

|

TRANSLATION:

May He Who grants salvation to kings and dominion to rulers,

May He Who grants salvation to kings and dominion to rulers,

Whose kingdom is a kingdom spanning all eternity,

Who releases David, his servant, from the evil sword,

Who places a road in the sea and a path in the mighty

waters –

May He bless, protect, guard, assist, elevate, exalt,

and lift upwards

Our master CZAR NIKOLAI ALEXANDROVICH,

With his wife, the honorable CZARINA ALEXANDRA

FEODOROVNA

Their son, the crown prince ALEXI NIKOLAIOVICH

And his mother, the honorable CZARINA MARIA FEODORAVNA

And the entire house of our king, may their glory be

exalted.

May the King of kings in His mercy give him life, and

protect him,

And save him from every trouble, woe and injury.

May nations submit under his feet, and may his enemies

fall before him,

And may he succeed in whatever he endeavors.

May the King of kings, in His mercy, grant compassion

in his heart

and the heart of all his advisors

To do favors for us and for all Israel, our brethren.

In his days and in our days, may Judah be saved, and

may Israel dwell securely,

And may the Redeemer come to Zion.

So may it be His

will – and we say: AMEN.

This prayer is so strange as to be

almost comical. You remember in Fiddler on the Roof,

when someone asks the rabbi, “Is there a blessing for the Czar?” He responds:

“A blessing for the Czar? Of

course – may God bless and keep the Czar …. Far away from us!” And in fact, there IS a prayer for the Czar,

or whoever the ruler happened to be, in traditional siddurim. Over the course of five centuries, hundreds of

prayerbooks have included a version of the prayer above, with the name of the

current leader inserted.

Why did Jews

say prayers like this? One objective

could have been to curry favor with the king. Jews tended to rely upon the king to ensure

their safety, and in fact, Jews tended to fare better in places where the king

was strong. So this could have been a

prayer uttered in sincerity: a strong

king, even a moderately anti-Jewish one, was better for the Jews than a weak

king who would be overcome by the raging mob.

But most

observers understand prayers like this as examples of the political use of

liturgy, rather than as authentic expressions of religious devotion. The prayer is recited, and printed in the

prayerbook, simply to ensure that no one could accuse the Jews of disloyalty. Stringing together so many synonyms -- “may He

bless, safeguard, preserve, help, exalt, make great, extol, and raise high…” --

makes it sound like the community is trying to make a point, rather than simply

praising someone they genuinely want to praise.

It is hard to imagine that Jewish communities that had been terrorized

by Czar Nicholas II and the previous Czars would have prayed without irony, “May

his enemies fall before him.” After all,

who were those enemies?! But no matter

how cruelly they were mistreated, they still needed to create an illusion of

respect for the authorities.

One line

towards the end of the prayer, however, appears to be an utterly serious plea: “May the King of kings, in His mercy, grant compassion

in his heart and the heart of all his advisors to do favors [or ‘acts of

goodness’] for us and for all Israel, our brethren.” Knowing

that this supremely powerful

monarch could essentially do as he wished with the Jewish people, the only hope

for the Jewish community was to pray for him to be compassionate. The fate of the Jewish community depended not

upon “rights,” but upon the “tovot” – “favors” that the ruling authorities

could choose to grant to them.

This prayer

summed up the relationship between Jewish communities and the non-Jewish

authorities quite well, for hundreds of years. But in the second half of the 18th

century, the situation began to change. The

change came first in French synagogues, where some communities began, after the

French Revolution and the emancipation of the Jewish community, to recite a new

form of the Prayer for the Government that was not focused on the King as an

individual.

But it was in the United States that many Jews came to realize that their assumptions about their relationship with the government needed to be thoroughly revised. We see evidence of these revisions in prayer customs and prayerbooks almost immediately after American independence.

The Jewish

community in Colonial America was tiny. In

the New York area, the only synagogue was Shearith Israel – the Spanish and

Portuguese Synagogue. Thankfully, that

community, which still exists today, preserved very good records of their

liturgical practice. Soon after the Declaration

of Independence in 1776, there was a change in liturgical practice at Shearith

Israel. While they did not change the text

of the prayer for the government, they decided that henceforth, instead of standing

up for that prayer, now they would sit down. This itself communicates a difference about

the model of government and the Jewish relationship to power: In the new United States, Jews can respect

the government without having to resort to flattery of its leaders.[1]

Another early

American siddur, written by Solomon Henry Jackson in 1826, contains two

different versions of the prayer: one

version for when Congress is in session, and a different version for when

Congress is on recess. The difference

is, when Congress is in recess, they aren’t your leaders, so there’s no reason

to pray for them. This could be

understood as an additional demonstration of a non-hierarchical and

non-deferential relationship with the ruling authorities. Additionally, the Jackson siddur version includes

a line blessing “the people.” What had always

been a prayer for the King and a prayer for the Government was now being

transformed into a prayer for the Country.

|

Sefardic prayerbook of Solomon Henry

Jackson, NYC, 1826

(scan from agmk.blogspot.com)

|

While there have been multiple versions of the Prayer for

the Government in American siddurim, one version that has stood the test of

time and has actually been reproduced, very close to the original, in every official

Conservative and Reconstructionist prayerbook for the past 85 years. This is the prayer by Rabbi Louis Ginzberg of

the Jewish Theological Seminary, composed back in 1927 for the Fesival

Prayer Book, the first liturgical publication of the Conservative Movement.

Ginzberg’s prayer reflects a growing realization that the

United States is a different kind of Diaspora. The leaders of the United States were not

rulers to be feared. Jews in the United

States were not an oppressed and barely tolerated minority. Rather, Jews were invited to be full partners

in this society, to come to the table to help to make decisions, to shape its

policy, and culture, and values. In the

United States, Jews do not need to pray merely that the rulers will show

fairness and compassion to the Jews. Rather,

a prayer for the United States should convey that this is a society of which

the Jewish community is an integral and valued part, and that this society upholds

– at least in theory, and often in practice – values that we passionately uphold,

such as liberty for all people, and tolerance of dissent. The overwhelming agenda of Rabbi Ginzberg’s

prayer is to show that the United States is made up of diverse ethnicities and

religions, and to pray that these different races and creeds will get along and

establish a society based on tolerance and freedom.

This country has numerous

imperfections. We continually strive to

make it ever more just and ever more equal. But sometimes it takes a glance at a siddur

from 1914 to remind me just how different, just how unprecedented, the

American Jewish experience has been in the sweep of Jewish history, and how gratefully I ask for God's blessings for this country.

[1] Jonathan

Sarna, “Jewish Prayers for the U.S. Government: A Study in the Liturgy of

Politics and the Politics of Liturgy,” in Karen Halttunen and Lewis Perry, ed.,

Moral Problems In American Life: New

Perspectives On Cultural History (Cornell University Press, 1998), p. 206.

Most interesting about the Ginzberg prayer is the principle of American exceptionalism ie that the US is somehow an "influence for good throughout the world, uniting all people in peace and freedom" This is a Jeffersonian idea that faded in the mid-19th century but that was in full flower from the post-WWI period onwards. Ironically, it's been the cause of a huge amount of damage around the world, as the US decided on what its "influence for good" meant for the governments of other countries. But the prayer's assumption that the US has an almost messianic power in the world is uniquely American.

ReplyDeleteThis is a good point. And in fact, if anything, Ginzberg's original version was even more "exceptionalist." The following words (Hebrew and English) were in his original version from 1927 and are also found in the 1946 Sabbath and Festival Prayerbook, but have been removed in later versions: המשתוקקים לראותה אור לכל הגוים.....

ReplyDelete“Fulfill the yearning of all the people of our country to speak proudly in its honor. Fulfill their desire to see it become a light to all nations.” The use of the Biblical phrase 'אור גויים,' 'light of nations' or 'light to the nations,' to refer (even aspirationally) to the United States is especially striking. Thanks for your comment.

That the US (of America, not Africa or Mexico) has a (NOT "almost") messianic power in the world is a basic premise of the beliefs of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (the LDS, or "Mormons")

ReplyDeleteAs for who decides what "influence for good" means, the Latter-day Saints also recognize that power corrupts - but their cannon states it with slightly greater precision, "(Doctrine and Covenants | Section 121:39) "We have learned by sad experience that it is the nature and disposition of almost all men, as soon as they get a little authority, as they suppose, they will immediately begin to exercise unrighteous dominion."