"Noah Voters and Abraham Voters" (Rosh haShanah 2012)

(Parts of this sermon are adapted from my reflections from July 4, http://rabbischeinberg.blogspot.com/2012/07/blessing-for-czar-in-honor-of.html.

It’s time for show and tell.

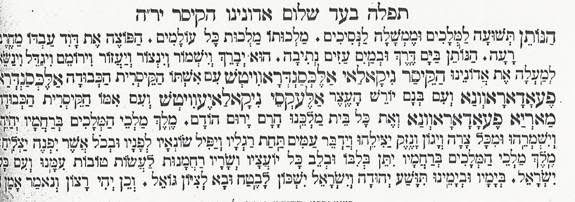

Let me tell you about this book, which some of you have seen before.

This book has been in the possession of our congregation since it was founded in 1905.

It’s a High Holiday Mahzor -- published in the Lithuanian city of Vilna, today Vilnius, in the year 1914.

But suppose you didn’t know that. Suppose the title page with the copyright information had been missing.

When you look at an old Jewish prayerbook, how can you figure out when and where it was published?

Let me show you. I am reading now from page 194-

a page immediately before the Torah is returned to the ark.

|

TRANSLATION:

May He Who grants salvation to kings and dominion to rulers,

Whose kingdom is a kingdom spanning all eternity….

May He bless, protect, guard, assist, elevate, exalt, and lift upwards

Our master CZAR NIKOLAI ALEXANDROVICH,

With his wife, the honorable CZARINA ALEXANDRA FEODOROVNA

Their son, the crown prince ALEXI NIKOLAIOVICH

And his mother, the honorable CZARINA MARIA FEODORAVNA

And the entire house of our king, may their glory be exalted.

May the King of kings in His mercy give him life, and protect him,

And save him from every trouble, woe and injury.

May nations submit under his feet, and may his enemies fall before him,

And may he succeed in whatever he endeavors.

May the King of kings, in His mercy, grant compassion in his heart

and the heart of all his advisors

To do favors for us and for all Israel, our brethren.

In his days and in our days, may Judah be saved, and may Israel dwell securely,

And may the Redeemer come to Zion. So may it be His will – and we say: AMEN.

So now you know -- when in Fiddler on the Roof, they ask the Rabbi,

“Is there a blessing for the Czar?”

It’s actually no joke. There IS a blessing for the Czar.

or the king, or the emperor, or whoever’s dominion Jews were living under at any particular time.

Some of you have heard me read from this or other old prayerbooks

especially on the Shabbat closest to July 4.

It has become for me a meaningful way to celebrate July 4

because it reminds me just how unprecedented

the Jewish experience has been in America.

Listen to how obsequious these words are:

May He bless, protect, guard, assist, elevate, exalt, and lift upwards.

especially when you think about what the relationship those leaders actually had with the Jewish minorities in their midst.

My favorite part is וייפול שונאיו לפניו “may their enemies fall before them.”

[Who do you think Czar Nicholas’s enemies were? US!]

Truly this does not look like a genuine heart-felt prayer.

This looks like a little moment of public relations in the midst of the prayer service -

just in case anyone should accuse the Jews of being insufficiently loyal and patriotic -

they can say, “What do you mean? Look at this prayer that we recite for the Czar every Shabbos in the synagogue!”

No matter how cruelly they were mistreated, they still needed to create an illusion of respect for the authorities.

So what happened when Jews came to the United States?

For most Jews, for the very first time, they were confronted with a system of government

in which they had a say.

in which their relationship with the government was not one of ‘us and them,’

or, worse, ‘us vs. them,’

but where members of the Jewish community itself were invited to have a voice in the political process.

Soon it became clear that this new land demanded a new kind of prayer for its new kind of government and new kind of society.

We take it for granted today, but there is virtually no other era in Jewish history

when a diaspora Jewish community felt that it had a measure of political control over its fate.

And as a result, most Jewish communities in the United States, including ours,

recite a completely different version of the prayer for the country

than the one I just read.

Its focus is not on deference and servility to the leadership,

and praying that the leaders will see fit to do favors to the Jewish community.

Because the leaders are US – or the ones WE help to choose.

Rather, this new prayer focuses on the dreams of justice and equity,

dreams that the Jewish community shares with our neighbors.

As I said, I have often described the history of the Jewish prayer for the government

near July 4,

but this story seems especially relevant at this time of year,

as we approach a presidential election --

the quintessential demonstration of the difference between how our ancestors were governed since time immemorial, and how we are governed today.

Now, you know that there are some congregations, Christian and Jewish,

where shortly before the election,

the spiritual leader gathers the flock together

and basically -- tells them exactly how they should vote.

Now what may be surprising to you -

is that that is exactly what I am going to do for the rest of this sermon:

Speaking on behalf of Jewish tradition as I understand it,

I am going to tell you -- how to vote.

I’m seeing some of you get a little nervous.

Especially the USH board members, who are probably terrified that I am about to say or do something that will jeopardize our 501c3 tax-exempt status.

So let me put your mind at ease. I of course am not going to communicate who you should vote FOR.

but is there a Jewish way to vote? Absolutely.

How could there be a Jewish way to eat, a Jewish way to wear clothing,

a Jewish way to engage in business practices, a Jewish way to speak, a Jewish way to rest,

but not a Jewish way to vote?!

If Judaism is a civilization in every sense of the word -

If Jewish law and tradition and values inform and enrich every aspect of our lives -

then certainly there are MORE Jewish ways to vote - and LESS Jewish ways to vote.

Now you may find it surprising that Jewish tradition would have anything to say about voting, considering how new we usually think that democracy is.

But actually, the idea of deciding important matters according to majority vote

has a long history in Jewish tradition.

In the time of the Talmud, we read about how civil and criminal trials were decided by a jury of one’s peers.

It’s described in the Talmud as a panel of 23 judges, but the qualifications of such a judge make it essentially equivalent to a jury trial today -

meaning that each person who was considered a full member of the society

participated actively in the judicial process.

And many medieval Jewish communities were self-governing, and elected their leadership, through community elections that were decided by majority vote,

and those leaders often constituted a municipal council that would govern by majority vote - just like some other city councils with which some of us may be familiar.

Those of you who are on our congregational email list know that before every election,

whether it’s a presidential election, or the election for Hoboken School Board, or anything in between,

I send out a reminder of the poll hours, and I also send a kavvanah - a meditation, in Hebrew and English, that one can say before voting.

There is a Jewish mystical tradition of reciting such a kavvanah, meditation, before performing any mitzvah - any commandment - as an opportunity to pause and take note of the holiness of the moment.

This kavvanah, which I adapted from my colleague Rabbi David Seidenberg, reads in part:

My favorite part is וייפול שונאיו לפניו “may their enemies fall before them.”

[Who do you think Czar Nicholas’s enemies were? US!]

Truly this does not look like a genuine heart-felt prayer.

This looks like a little moment of public relations in the midst of the prayer service -

just in case anyone should accuse the Jews of being insufficiently loyal and patriotic -

they can say, “What do you mean? Look at this prayer that we recite for the Czar every Shabbos in the synagogue!”

No matter how cruelly they were mistreated, they still needed to create an illusion of respect for the authorities.

So what happened when Jews came to the United States?

For most Jews, for the very first time, they were confronted with a system of government

in which they had a say.

in which their relationship with the government was not one of ‘us and them,’

or, worse, ‘us vs. them,’

but where members of the Jewish community itself were invited to have a voice in the political process.

Soon it became clear that this new land demanded a new kind of prayer for its new kind of government and new kind of society.

We take it for granted today, but there is virtually no other era in Jewish history

when a diaspora Jewish community felt that it had a measure of political control over its fate.

And as a result, most Jewish communities in the United States, including ours,

recite a completely different version of the prayer for the country

than the one I just read.

Its focus is not on deference and servility to the leadership,

and praying that the leaders will see fit to do favors to the Jewish community.

Because the leaders are US – or the ones WE help to choose.

Rather, this new prayer focuses on the dreams of justice and equity,

dreams that the Jewish community shares with our neighbors.

As I said, I have often described the history of the Jewish prayer for the government

near July 4,

but this story seems especially relevant at this time of year,

as we approach a presidential election --

the quintessential demonstration of the difference between how our ancestors were governed since time immemorial, and how we are governed today.

Now, you know that there are some congregations, Christian and Jewish,

where shortly before the election,

the spiritual leader gathers the flock together

and basically -- tells them exactly how they should vote.

Now what may be surprising to you -

is that that is exactly what I am going to do for the rest of this sermon:

Speaking on behalf of Jewish tradition as I understand it,

I am going to tell you -- how to vote.

I’m seeing some of you get a little nervous.

Especially the USH board members, who are probably terrified that I am about to say or do something that will jeopardize our 501c3 tax-exempt status.

So let me put your mind at ease. I of course am not going to communicate who you should vote FOR.

but is there a Jewish way to vote? Absolutely.

How could there be a Jewish way to eat, a Jewish way to wear clothing,

a Jewish way to engage in business practices, a Jewish way to speak, a Jewish way to rest,

but not a Jewish way to vote?!

If Judaism is a civilization in every sense of the word -

If Jewish law and tradition and values inform and enrich every aspect of our lives -

then certainly there are MORE Jewish ways to vote - and LESS Jewish ways to vote.

Now you may find it surprising that Jewish tradition would have anything to say about voting, considering how new we usually think that democracy is.

But actually, the idea of deciding important matters according to majority vote

has a long history in Jewish tradition.

In the time of the Talmud, we read about how civil and criminal trials were decided by a jury of one’s peers.

It’s described in the Talmud as a panel of 23 judges, but the qualifications of such a judge make it essentially equivalent to a jury trial today -

meaning that each person who was considered a full member of the society

participated actively in the judicial process.

And many medieval Jewish communities were self-governing, and elected their leadership, through community elections that were decided by majority vote,

and those leaders often constituted a municipal council that would govern by majority vote - just like some other city councils with which some of us may be familiar.

Those of you who are on our congregational email list know that before every election,

whether it’s a presidential election, or the election for Hoboken School Board, or anything in between,

I send out a reminder of the poll hours, and I also send a kavvanah - a meditation, in Hebrew and English, that one can say before voting.

There is a Jewish mystical tradition of reciting such a kavvanah, meditation, before performing any mitzvah - any commandment - as an opportunity to pause and take note of the holiness of the moment.

This kavvanah, which I adapted from my colleague Rabbi David Seidenberg, reads in part:

הַרֵינִי מוּכָן וּמְכָוֵון בְּהַצְבָּעָתִי הַיוֹם

לִדְרֹש שָׁלוֹם בַּעָד הַמְדִינָה הַזֹאת

With my vote today, I mindfully intend to seek peace for my city and my nation.....

ׁתִּתֵן לְבָב חָכְמָה

לְמִי שֶׁאָנוּ בּוֹחֲרִים הַיוֹם

וְתִשָׂא עַלֵינוּ מֶמְשָלָה לְטוֹבָה וְלִבְרָכָה

May You give a wise heart to whoever we elect today,

and may You help us to establish a government for goodness and blessing

to bring justice and well-being to all the inhabitants of this city and this nation.

And truly, that is step 1 of voting Jewishly.

Voting Jewishly means voting with consciousness -

consciousness of our good fortune to live at a time and place where we participate in the shaping of our political fate.

and consciousness that voting is the fulfillment of a mitzvah- a commanded holy act to establish justice and peace in our communities.

But does Judaism have anything to say about how we select our candidates?

again, I answer: if selecting candidates for public office is a matter of significance,

how could Judaism NOT take a stand on how one is supposed to do it?!

Let me suggest to you that there are two kinds of voters:

we could call them “Noah voters” and “Abraham voters.”

A few weeks from now in our torah reading cycle,

we will read about Noah -- who, as we know, is told by God

that the people in his society are wicked,

and God intends to destroy them,

but God intends to save Noah. -

and may You help us to establish a government for goodness and blessing

to bring justice and well-being to all the inhabitants of this city and this nation.

And truly, that is step 1 of voting Jewishly.

Voting Jewishly means voting with consciousness -

consciousness of our good fortune to live at a time and place where we participate in the shaping of our political fate.

and consciousness that voting is the fulfillment of a mitzvah- a commanded holy act to establish justice and peace in our communities.

But does Judaism have anything to say about how we select our candidates?

again, I answer: if selecting candidates for public office is a matter of significance,

how could Judaism NOT take a stand on how one is supposed to do it?!

Let me suggest to you that there are two kinds of voters:

we could call them “Noah voters” and “Abraham voters.”

A few weeks from now in our torah reading cycle,

we will read about Noah -- who, as we know, is told by God

that the people in his society are wicked,

and God intends to destroy them,

but God intends to save Noah. -

God commands Noah to build an ark,

make it so many cubits by so many cubits, and cover it with pitch, and save his family and an assortment of animals.

make it so many cubits by so many cubits, and cover it with pitch, and save his family and an assortment of animals.

And this is exactly what Noah proceeds to do.

And nowhere in the torah is there any indication that Noah hesitates for a moment,

or expresses concern about the people who will be washed away.

Whatever happens, Noah knows that he and his family will be safe

And then, the week after we read about Noah,

we learn about Abraham, the founder of the Jewish people, about whom we also read this morning.

But shortly before our torah reading this morning

was another relevant episode in Abraham’s life.

God approaches Abraham and says to him: the residents of the cities of Sodom and Gemorrah

are exceedingly wicked - and I intend to destroy them.

And how does Abraham react?

This news sends Abraham into a rage.

“Far be it from you to do such a thing, to wipe away the innocent together with the wicked!”

השופט כל הארץ לא יעשה משפט!!

“Won’t the judge of all the earth deal justly?!”

And Abraham issues a demand that if there are even 50 righteous people in the city, that God should relent.

And God does relent.

And then, of course, Abraham enters bargaining mode. “But God, what if there aren’t 50 righteous people, but only 45? What about 40? 30? 20?

And Abraham extracts a promise from God that if there are even TEN righteous people in the city,

then God will not destroy the city.

[This is how you can tell that Abraham is the founder of the Jewish people.

He’s the first one in the Torah to demonstrate this degree of chutzpah.]

But why did Abraham care so much about the people of Sodom and Gemorrah?!

The answer is: because they were his neighbors.

Abraham is simply a person who is animated by the mission ושמרו דרך ה’ לעשות צדקה ומשפט -

"to follow the ways of God, to act with righteousness and justice."

And in contrast to Noah, who is thinking about himself,

Abraham makes his decisions based on the fate of his neighbors.

And those are the two kinds of voters.

Some voters are like Noah, making their decisions based exclusively or primarily on their own needs and their own self-interest.

If I’m a Noah voter, I care primarily about me- and those in the same boat as me.

And some voters are like Abraham. Of course, they need not be oblivious to their own self-interest. But they have a broader vision, not only thinking of themselves. They truly take seriously their mandate

that the decisions they make about government are holy decisions -

that they are the way that we enact justice in the world -

and so they think not only of themselves, but also of their neighbors – taking a special interest in those who are most vulnerable.

Now I categoricially promise you that this distinction between Noah voters and Abraham voters

is not an endorsement in disguise.

The Democratic Party in the United States has plenty of Abraham voters and plenty of Noah voters.

And the Republican Party in the United States has plenty of Abraham voters and plenty of Noah voters.

And judging from the political advertising, it appears that both political parties are spending much more time and energy going after the Noah voter demographic.

So how can you tell which kind of voter you are?

Someone who votes based primarily on whatever party will be most likely to reduce their own taxes - is a Noah voter.

Someone who votes based primarily on his or her individual answer to the question “Am I better off or worse off than I was four years ago?” is a Noah voter.

And someone who says, when I vote, I need to bear in mind what policies I think will pave the way for greater success, and greater justice -

not just for me, but for my society;

not just for my country, but for my world;

and not just for my current generation, but also for future generations, even after I am gone - -

that’s an Abraham voter.

And nowhere in the torah is there any indication that Noah hesitates for a moment,

or expresses concern about the people who will be washed away.

Whatever happens, Noah knows that he and his family will be safe

And then, the week after we read about Noah,

we learn about Abraham, the founder of the Jewish people, about whom we also read this morning.

But shortly before our torah reading this morning

was another relevant episode in Abraham’s life.

God approaches Abraham and says to him: the residents of the cities of Sodom and Gemorrah

are exceedingly wicked - and I intend to destroy them.

And how does Abraham react?

This news sends Abraham into a rage.

“Far be it from you to do such a thing, to wipe away the innocent together with the wicked!”

השופט כל הארץ לא יעשה משפט!!

“Won’t the judge of all the earth deal justly?!”

And Abraham issues a demand that if there are even 50 righteous people in the city, that God should relent.

And God does relent.

And then, of course, Abraham enters bargaining mode. “But God, what if there aren’t 50 righteous people, but only 45? What about 40? 30? 20?

And Abraham extracts a promise from God that if there are even TEN righteous people in the city,

then God will not destroy the city.

[This is how you can tell that Abraham is the founder of the Jewish people.

He’s the first one in the Torah to demonstrate this degree of chutzpah.]

But why did Abraham care so much about the people of Sodom and Gemorrah?!

The answer is: because they were his neighbors.

Abraham is simply a person who is animated by the mission ושמרו דרך ה’ לעשות צדקה ומשפט -

"to follow the ways of God, to act with righteousness and justice."

And in contrast to Noah, who is thinking about himself,

Abraham makes his decisions based on the fate of his neighbors.

And those are the two kinds of voters.

Some voters are like Noah, making their decisions based exclusively or primarily on their own needs and their own self-interest.

If I’m a Noah voter, I care primarily about me- and those in the same boat as me.

And some voters are like Abraham. Of course, they need not be oblivious to their own self-interest. But they have a broader vision, not only thinking of themselves. They truly take seriously their mandate

that the decisions they make about government are holy decisions -

that they are the way that we enact justice in the world -

and so they think not only of themselves, but also of their neighbors – taking a special interest in those who are most vulnerable.

Now I categoricially promise you that this distinction between Noah voters and Abraham voters

is not an endorsement in disguise.

The Democratic Party in the United States has plenty of Abraham voters and plenty of Noah voters.

And the Republican Party in the United States has plenty of Abraham voters and plenty of Noah voters.

And judging from the political advertising, it appears that both political parties are spending much more time and energy going after the Noah voter demographic.

So how can you tell which kind of voter you are?

Someone who votes based primarily on whatever party will be most likely to reduce their own taxes - is a Noah voter.

Someone who votes based primarily on his or her individual answer to the question “Am I better off or worse off than I was four years ago?” is a Noah voter.

And someone who says, when I vote, I need to bear in mind what policies I think will pave the way for greater success, and greater justice -

not just for me, but for my society;

not just for my country, but for my world;

and not just for my current generation, but also for future generations, even after I am gone - -

that’s an Abraham voter.

There’s something else we can notice about the contrast between Noah and Abraham.

When God gives them each the news about the fate of their neighbors:

Noah doesn’t speak up. And Abraham, boy does he speak up.

Abraham is the paradigm of combative engagement with leadership.

And this reminds of another quality of Abraham voters -the model to which I believe that Jewish tradition encourages us to aspire.

And that is: that political discourse should be vigorous! It should be passionate, heartfelt!

Ever since the Talmud, which has been described as less a collection of sacred conclusions

and more - a collection of sacred arguments –

Jewish tradition has never encouraged people to shrink away from disputes.

When we say ‘two Jews, three opinions,’ we’re not kidding.

After all, leaders so often deal with life-and-death issues. Why SHOULDN’T we be passionate!?

But political discourse should also be scrupulously truthful, and scrupulously respectful.

It should remind us that it’s all about a holy process,

that voting, and governing, is a holy act.

No matter what side of the political debate you are on, on one thing we can agree:

this is not a banner year for truth in politics. or for respect in politics.

From demonization and ridicule of opponents -- to shading the truth --

to taking words, innocently stated, out of their context --

We have come to tolerate a level of political discourse that we would NEVER tolerate

in "real life."

if we used techniques like this to talk to our friends, we wouldn’t have any friends left.

The character of our leaders matters -

and I have in the past hesitated to vote for candidates with whom I agreed on the issues

if I felt that they were conducting a campaign that gave me concerns about their character.

We notice something interesting about Abraham: In his opening salvo in his debate with God, Abraham nearly loses his cool, saying

חלילה לך - Far be it from you!

When we say ‘two Jews, three opinions,’ we’re not kidding.

After all, leaders so often deal with life-and-death issues. Why SHOULDN’T we be passionate!?

But political discourse should also be scrupulously truthful, and scrupulously respectful.

It should remind us that it’s all about a holy process,

that voting, and governing, is a holy act.

No matter what side of the political debate you are on, on one thing we can agree:

this is not a banner year for truth in politics. or for respect in politics.

From demonization and ridicule of opponents -- to shading the truth --

to taking words, innocently stated, out of their context --

We have come to tolerate a level of political discourse that we would NEVER tolerate

in "real life."

if we used techniques like this to talk to our friends, we wouldn’t have any friends left.

The character of our leaders matters -

and I have in the past hesitated to vote for candidates with whom I agreed on the issues

if I felt that they were conducting a campaign that gave me concerns about their character.

We notice something interesting about Abraham: In his opening salvo in his debate with God, Abraham nearly loses his cool, saying

חלילה לך - Far be it from you!

But then, in Abraham’s SECOND approach to God -

he begins

הנה נא הואלתי לדבר אל אדני ואנכי עפר ואפר

Here now, I have taken it upon myself to speak to God, when I am but dust and ashes.

He continues the bargaining with no less passion,

but he has walked back his shrill tone,

he is acknowledging his own fallibility, as he approaches God with humility.

he begins

הנה נא הואלתי לדבר אל אדני ואנכי עפר ואפר

Here now, I have taken it upon myself to speak to God, when I am but dust and ashes.

He continues the bargaining with no less passion,

but he has walked back his shrill tone,

he is acknowledging his own fallibility, as he approaches God with humility.

And in our current political climate, that humility would be useful.

More than 40 years ago, the illustrious Jewish theologian Martin Buber described the political tenor of his times:

The human world is today, as never before, split into two camps, each of which understands the other as the embodiment of falsehood and itself as the embodiment of truth. . . . Each side has assumed monopoly of the sunlight and has plunged its antagonist into night, and each side demands that you decide between day and night. . . . ” [Martin Buber, “Hope for this Hour”]

And sometimes we are drawn into picturing this country in such Manichean terms.

But the overwhelming majority of issues at stake in the current election,

Or any American election,

Are issues on which reasonable people can disagree.

What should health care look like in a society like ours?

What tax rates are appropriate for people and corporations at various points on the income scale?

What’s the best way to safeguard against threats to our security?

What tax rates are appropriate for people and corporations at various points on the income scale?

What’s the best way to safeguard against threats to our security?

What should be the tenor of the relationship between the United States and Israel?

What’s the best way to ensure that Iran doesn’t acquire nuclear weapons?

What’s the best way to ensure that Iran doesn’t acquire nuclear weapons?

On these and other issues, analysts have noted that people on either side of the political divide are often not interested in listening to each other –

That “questions from one side to the other are prosecutorial,

rather than genuine requests for understanding;

rather than genuine requests for understanding;

Complex issues are defined in dichotomous, 'win-lose' ways,

with nuances and intermediate positions suppressed.

There is little genuine listening to perspectives from the 'other side.' "

(Herzig and Chasin, "Fostering Dialogue Across Divides")

We may have our own strongly held answers to these questions, and we may disagree passionately with others’ perspectives,

with nuances and intermediate positions suppressed.

There is little genuine listening to perspectives from the 'other side.' "

(Herzig and Chasin, "Fostering Dialogue Across Divides")

We may have our own strongly held answers to these questions, and we may disagree passionately with others’ perspectives,

But when we are honest with ourselves, we must concede that on each of these issues, there’s a range of positions on which reasonable people disagree.

For centuries, Judaism has pioneered a style of dialogue between people who disagree that encourages the retention of respect, even when there is no common ground.

We strive to remember that each person is created in the image of God,

We strive to remember that each person is created in the image of God,

Even people with whom we passionately disagree.

One of the outstanding American Orthodox rabbis of the 20th century, Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik, expressed this value, saying: "I may attack a certain point of view which I consider false, but I will never attack a person who preaches it. I have always a high regard for the individual who is honest and moral, even when I am not in agreement with him. Such a relation is in accord with the concept of kavod habriyot,[the honor due to every individual].”

This kind of communication is what Pirkei Avot, the Ethics of the Fathers, describes as a מחלוקת לשם שמים – an argument for the sake of heaven.

And THAT is the paradigm for a Jewish disagreement on any topic.

This kind of communication is what Pirkei Avot, the Ethics of the Fathers, describes as a מחלוקת לשם שמים – an argument for the sake of heaven.

And THAT is the paradigm for a Jewish disagreement on any topic.

There are some religious traditions that insist that holiness in this world is inachievable –

That the only way to live a holy life is to flee from the necessarily mundane, dirty parts of our world.

But Judaism has always insisted that this is a cop-out –

That it’s our job to BRING holiness to the earth, no matter how challenging a task that may appear.

We can bring holiness to the earth – every time we bring a higher level of consciousness to our act of voting.

Or every time we alleviate the suffering of others.

Or every time we bridge a disagreement, or turn an enemy into a friend.

Or, ideally, every time we engage in the political process.

This is how Hasidic master Rabbi Hanoch of Alexander used to understand the famous verse from the Psalms:

השמים שמים לה'

The heavens are Gods’ heavens,

השמים שמים לה'

The heavens are Gods’ heavens,

are already godly in character.

והארץ נתן לבני אדם.

but God has given the earth to human beings.

God gave it to us so that we could make something godly out of it.

God gave it to us so that we could make something godly out of it.

Only when we work together do we have a chance to succeed.

As we read repeatedly in the Mahzor over these holidays,

As we read repeatedly in the Mahzor over these holidays,

ויעשו כולם אגודה אחת לעשות רצונך בלבב שלם

May all of us, of all backgrounds and perspectives

. be bound together, carrying out your will whole-heartedly.”

Comments

Post a Comment